Why the Second Amendment does not protect hunting animals

An Animal Rights Article from All-Creatures.org

FROM

Merritt and Beth Clifton, Animals 24-7

February 2018

The only form of “hunting” that concerned the 2nd Amendment authors was catching fugitive slaves.

Collage by Beth Clifton

The only form of “hunting” that concerned the 2nd Amendment authors was

catching fugitive slaves

No part of the U.S. Constitution seems better known to hunters, or is more

vehemently defended by pro-hunting organizations, than the single sentence

that is the whole of the Second Amendment:

“A well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free state,

the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.”

Yet the Second Amendment includes no mention of hunting, either direct or

implicit.

Hunting animals could be entirely abolished by law––though the prospect is

unlikely––without at all infringing upon the Second Amendment.

Firearms rarely used for hunting in 1791

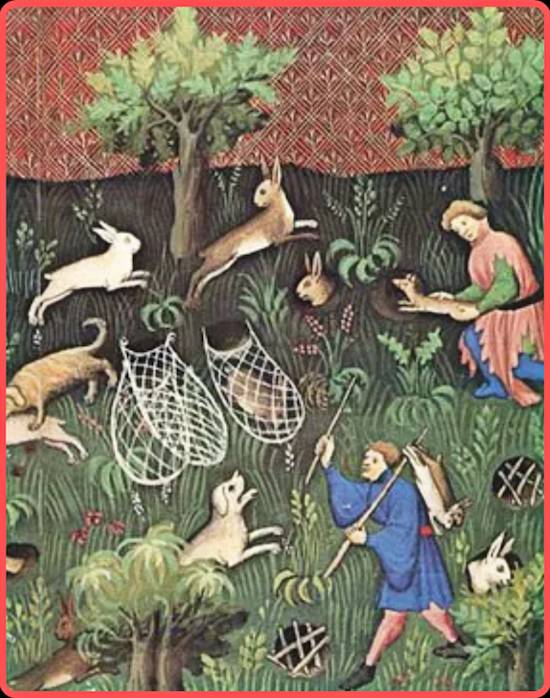

Rabbit hunting with a ferret and hounds, painted by Gaston Pheobus, the

Count of Foix and Viscount of Bearn, circa 1387-1391.

Indeed, firearms were rarely used for hunting when the Second Amendment was

adopted, in 1791.

Cannon-like “fowling pieces” had been introduced by wealthy European estate

owners about 200 years earlier.

As of 1791, however, most “fowling pieces” were still too heavy to be

carried or aimed easily except on the cleared and drained estates of the

very wealthy, where captive birds were raised to be shot for sport.

Fowlers in mucky cultvated fieds, swamps, and woodlands hunted mostly for

meat and feathers, using the same techniques used since before the

beginnings of written history: nets, snares, slingshots, and pots of lime

cement. Lime cement was used to paint branches, gluing unwary birds to be

clubbed when they landed.

Clubs were used more than rifles

Snares and clubs were also the weapons most used to hunt “small game,” such

as rabbits, and even some larger animals, including deer.

Muskets, of limited range and incapable of rapid fire, were––like “fowling

pieces”––heavy, expensive, inaccurate, and therefore seldom used for

hunting.

Military use of muskets was rapidly superseded by the advent of rifles

between the French-and-Indian War of 1756-1763 and the American Revolution

of 1775-1783.

But rifles, though more accurate than muskets, remained costly, hard to use

against animals moving much faster than soldiers, and were rarely possessed

by civilians.

As guns became lighter and more accurate, hunting use proliferated.

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau, born in 1817, recalled in Walden (1854) that by his

youth, two generations after the passage of the Second Amendment, “Almost

every New England boy among my contemporaries [his father owned a pencil

factory] shouldered a fowling-piece between the ages of ten and fourteen.”

Thoreau went on to mention the common argument that “perhaps the hunter is

the greatest friend of the animals hunted, not excepting the Humane

Society,” bewildering historians, since the first humane society known to

have existed in the U.S. was not formed until four years later. The first

humane society known to have opposed hunting was incorporated ten years

after that.

Thoreau went on to describe in a rather muddled manner how he had given up

hunting, yet did not discourage boys from hunting, while wishing that “they

shall not find game large enough for them in this or any vegetable

wilderness.”

Humane societies rarely target hunting

Much like Thoreau, organized animal advocacy has historically taken a mixed

and muddled view of hunting deer and birds who are actually eaten, not just

shot for sport.

Humane societies in the 19th century provided the first impetus toward

protecting rare and threatened species, opposed pigeon shoots and other

massacres of captive animals, and stood against such obvious cruelties such

as leghold trapping, setting dogs on other animals, and clubbing baby seals

on the ice in front of their mothers.

Yet only in New York state, in the late 19th century, have traditional

humane societies sought to prohibit sport hunting entirely, and even that

short-lived but nearly successful movement was soon subsumed––or

coopted––into awkwardly collaborating with pro-hunting fronts to try to

protect habitat, restrict hunting seasons in a manner not injurious to

“game” populations, and limit hunting methods to those involving a “fair

chase” before the killing.

Trading guns for cameras

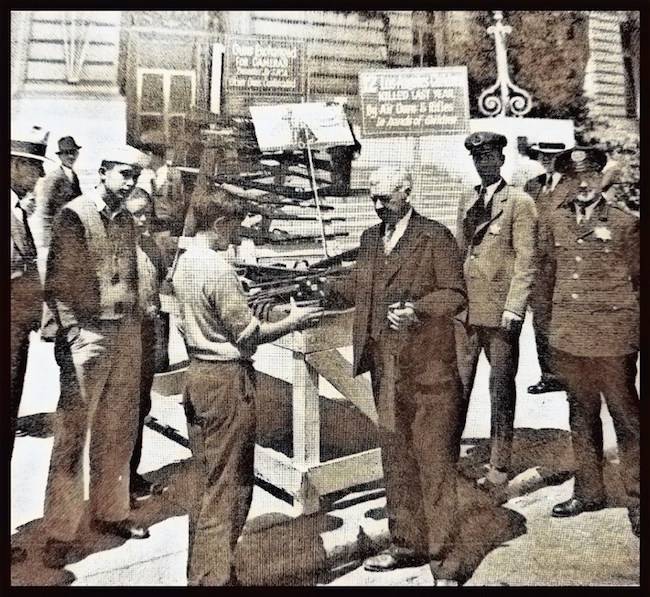

The San Francisco SPCA held this guns-for-cameras-swap in 1936.

From the 19th century to the emergence of the animal rights movement in the

late 20th century, almost nothing that animal advocacy organizations

espoused was not also endorsed by “hunter/conservationist” fronts, including

the 48 state chapters of the National Wildlife Federation, the Wilderness

Society, the National Audubon Society, and even the National Rifle

Association.

None of these organizations, for example, appear to have opposed humane

society programs of the mid-20th century which encouraged boys to exchange

their often dilapidated and dangerous firearms for cameras.

“Hunter harassment”

The most aggressive anti-hunting efforts in the U.S. during the 20th

century, by far, were the hunter harassment campaigns led by recently

resigned Humane Society of the U.S. president Wayne Pacelle in 1990-1994, as

then national director of the Fund for Animals.

The hunter harassment campaigns were modeled after the “hunt sabotage”

tactics used in Britain against fox hunting. But fox hunting involves

affluent mounted spectators and large numbers of ill-controlled hounds

running amok over miles of countryside, damaging crops, terrorizing wildlife

and anyone else in their path, often killing pets and livestock.

Attempts to disrupt deer and waterfowl hunts, practiced by ordinary

Americans in relatively out-of-the-way places, quickly backfired. Instead of

discouraging hunters from hunting, disrupting deer and waterfowl hunts

awakened hunters as a political constituency.

“Right to hunt”

By 1999 every U.S. state had passed anti-hunter harassment legislation.

Twenty states have since 1996 also guaranteed a “right” to hunt and fish in

their constitutions.

The only state recognizing such a “right” before 1996 was Vermont, where it

was established by the constitution of the Vermont Republic, an independent

nation from 1777 to 1791. The political dealing that created the “right” to

hunt and fish also abolished slavery and disbanded the Green Mountain Boys,

the “well-regulated Militia” which had been the chief military force within

the newly formed country.

Few deer hunters and waterfowlers use military-type weaponry, such as

semi-automatic rifles with large-capacity magazines, or heavy-caliber sniper

rifles. Few deer hunters and waterfowlers use handguns of any sort.

As then-National Rifle Association president Franklin Orth recognized in

Congressional testimony in 1964, “most sportsmen can live with” laws

restricting or prohibiting the possession and use of firearms that are

practical only for use in killing or threatening people.

What Thoreau meant

But politically mobilized hunters have historically helped the NRA and other

pro-gun organizations to maintain and expand their influence. Heavily funded

by the gun industry, pro-gun and pro-hunting groups tend to keep hunters in

a constant state of alarm that they may somehow lose their presumed “right”

to kill animals if the Second Amendment is interpreted as it always was

before 2008.

Yet, paradoxically, surveys of deer hunters and waterfowlers tend to find

that they have more in common with mainstream animal advocates––if not with

with vegans––than with most participants in forms of hunting such as

trapping, hounding, shooting prairie dogs just for target practice, and

massacring captive wildlife, including pigeons and cage-reared pheasants.

Deer hunters and waterfowlers, for example, tend to mention that they prefer

eating animals who had a natural life in the wild, over eating those who

were factory-farmed.

Such hunters are hunting chiefly for fun. They are not hunting just to avoid becoming vegetarian, or vegan. They are not latent animal rights activists. But neither are they engaging in overtly sadistic practices, involving victim animals who have little or no chance to escape, and are rarely eaten afterward.

The NRA needs hunters more than hunters need the NRA

Deer hunting and waterfowling appear to be dying out through declining

participation. Yet deer hunting and waterfowling have never been in real

danger of abolition by law, unlike the many more overtly and deliberately

cruel hunting practices which evade abolition only through the vigorous

defenses mounted by the NRA and other entities that depend on hunter support

for their political clout.

The NRA needs hunter support for its interpretation of the Second Amendment

much more than most hunters need either the NRA or the Second Amendment

itself. This is not a matter of hunter numbers so much as it is a matter of

population distribution, culture, and history.

Currently, hunters together with all members of their households constitute

less than 20% of the U.S. electorate, yet retain grossly disproportionate

political influence for two reasons, of which the support of the NRA is

actually the least of note.

Geography is influence

Well-funded as the NRA and other pro-gun organizations are, they would

have no more influence than many other marginal causes and factions if not

for geography.

There are now more vegetarians in the U.S. than licensed hunters, and are

even more vegans than participants in trapping, hounding, pigeon shooting,

and killing pen-raised trophy animals. Vegetarians and vegans, however, are

relatively concentrated in coastal metropolitan areas, overlapping perhaps a

dozen states, which mostly have not been in political sway for at least a

generation. No politician needs to cater to vegetarians and vegans as a key

“swing” constituency.

Hunters by contrast are broadly distributed throughout the conservative

rural and semi-rural “red” states of the South and the Rocky Mountain

regions. These now solidly Republican states were in the mid-19th century

the Confederate states and the portions of the then still wide open “wild

west” to which former slaveholders and landless ex-Confederate soldiers fled

by the tens of thousands after the U.S. Civil War ended slavery.

“Red” for “pro-gun”

Today, the combined human populations of six of the most strongly

pro-hunting states––––Wyoming, Vermont, North and South Dakota, Alaska, and

Montana––amount to less than the human populations of the Los Angeles and

San Francisco metropolitan areas. Yet those six states have 12 U.S.

Senators, while the entire state of California has just two.

Also among the states with the most hunters per capita are the “swing”

states of Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio,

Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Seven of these nine states supported Donald

Trump in 2016.

The disproportionality of hunter influence is so extreme that even though

polls have shown that up to 78% of all U.S. voters oppose hunting in

National Wildlife Refuges, at least 330 of the current 562 National Wildlife

Refuges now permit hunting––and more refuge hunting seasons were opened

during the Bill Clinton and Barack Obama administrations than in all

Republican administrations combined, as Democrats desperately sought to woo

hunter support from alignment with the far right-leaning gun lobby.

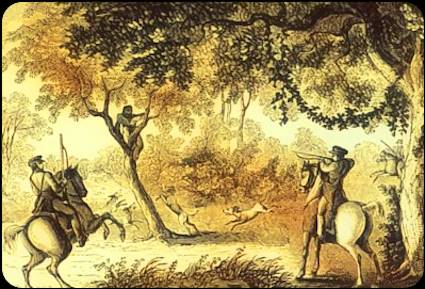

Fear of slave revolts

The fugitive slave Joe was captured, then allowed to escape to be hunted

for sport at the Broxton Bridge Plantation in South Carolina on July 5,

1853.

(Contemporary illustration)

The ploy did not succeed, not because the dwindling numbers of hunters have

not welcomed the opportunity to shoot up wildlife refuges, but because the

cultural and historical impetus toward gun ownership and militant assertions

of a “right” to keep any and all types of firearm really has little or

nothing to do with legal deer hunting or waterfowling.

Militant gun advocacy does, however, have deep roots in the fear of slave

revolts that led to the Second Amendment having been added to the Bill of

Rights in 1791, amid the political trade-offs that finally brought Vermont

into the U.S. as the 14th state.

Vermont scared the South

The admission of Vermont to the Union scared the South in two ways.

First, admitting Vermont made it the first state in which slavery was

prohibited, and increased the likelihood that the other northern states in

which slavery was strongly disapproved would soon also abolish it, as they

did.

Second, the Vermont Republic had disbanded the Green Mountain Boys militia

at the same time it abolished slavery and guaranteed residents the right to

hunt. The militia was replaced by the Green Mountain Continental Rangers,

allied with the Continental Congress and under federal rather than state

government command.

That scared the South because it set a strong precedent for disbanding the

militias which, in the plantation states, had long been chiefly engaged in

suppressing slave revolts.

The Georgia Militia

Explained Thom Hartmann for AlterNet in 2015, “In Georgia, for example, a

generation before the American Revolution, laws were passed in 1755 and 1757

that required all plantation owners or their male white employees to be

members of the Georgia Militia.”

Elaborated Roger Williams University law professor Carl T. Bogus in a 1998

article published by the University of California Law Review, “The Georgia

statutes required patrols, under the direction of commissioned militia

officers, to examine every plantation each month and authorized them to

search ‘all Negro Houses for offensive Weapons and Ammunition’ and to

apprehend and give twenty lashes to any slave found outside plantation

grounds.”

Continued Hartmann, “These two possibilities worried southerners like

James Monroe, George Mason (who owned over 300 slaves), and the southern

Christian evangelical, Patrick Henry,” who is ironically best remembered for

his 1775 declaration “Give me liberty, or give me death!”

“In this state there are 236,000 blacks”

“Their main concern,” Hartman explained, “was that Article 1, Section 8 of

the newly-proposed Constitution, which gave the federal government the power

to raise and supervise a militia, could also allow that federal militia to

subsume their state militias and change them from slavery-enforcing

institutions into something that could even, one day, free the slaves.”

There was already a well-established precedent, predating the American

Revolution, with antecedents in Roman times, for slaves to earn freedom

through military service.

Expressing concern that “In this state there are 236,000 blacks,” Patrick

Henry said, “If the country be invaded, a state may go to war, but cannot

suppress [slave] insurrections [under this new Constitution]. If there

should happen an insurrection of slaves, the country cannot be said to be

invaded. They cannot, therefore, suppress it without the interposition of

Congress.”

Congress responded by adopting the Second Amendment.

No change of interpretation for 217 years

The meaning of the words that “A well-regulated Militia being necessary to

the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms

shall not be infringed” went essentially undisputed for two centuries.

As former U.S. attorneys general Nicholas Katzenbach, Ramsey Clark, Elliot

Richardson, Edward Levi, Griffin Bell and Benjamin Civiletti jointly

declared in the Washington Post in 1992, “For more than 200 years, the

federal courts have unanimously determined that the Second Amendment

concerns only the arming of the people in service to an organized state

Militia: it does not guarantee immediate access to guns for private

purposes.”

Neither did the NRA dispute this, from formation in 1871 until after a

membership coup in 1977.

NRA promoted gun control

Testified then-NRA president and 1920 Olympic gold medalist for marksmanship

Karl T. Frederick, in support of the 1938 federal gun control law, which was

upheld unanimously by the U.S. Supreme Count in 1939 and reinforced by

Congress in 1968, “I have never believed in the general practice of carrying

weapons. I do not believe in the general promiscuous toting of guns. I think

it should be sharply restricted and only under licenses.”

Already the NRA and the parallel National Revolver Association had for

nearly two decades pushed state legislation requiring permits to carry

concealed weapons, adding five years to a prison sentence for using a gun in

committing a crime, banning non-citizens from buying a handgun, obliging gun

dealers to turn over sales records to police, and creating a waiting period

of from one to two days between buying a gun and getting it.

Eighteen states adopted such laws, now bitterly opposed by the NRA,

without visible opposition from hunters. The major pro-hunting organizations

of the era were themselves lobbying to establish hunting licenses, bag

limits, wildlife refuges, and restrictions on the types of arms and

techniques that could be used to hunt, at a time when the populations of

most hunted species were at or near low ebb.

“Traditional purposes”

The 1977 takeover of the NRA by pro-gun militants “resulted in a new harder

edged and more aggressive NRA,” recalled Washington University School of Law

adjunct professor Burton Newman in 2013. “The truth mattered not. The NRA

headquarters would now bear an abbreviated version of the Second Amendment:

‘The Right of the People to keep and Bear Arms Shall not be infringed.’ The

NRA amended the Constitution unilaterally to avoid even a hint that the

language pertaining to a Militia had any meaning. The law of the land spoke

otherwise.”

The U.S. Supreme Court in District of Columbia vs. Heller in 2008 altered

the traditional interpretation of the Second Amendment, Newman explained.

The Heller verdict held “that there existed an individual right to bear arms

only for traditional purposes.”

These “traditional purposes”, in the words of the U.S. Court of Appeals

for the D.C. Circuit decision that preceded the Supreme Court ruling,

included “hunting and self-defense in the home.”

Nothing in 2nd Amendment about either hunting or personal

self-defense

The five-to-four U.S. Supreme Court decision added nothing about hunting to

the U.S. Court of Appeals language. But Supreme Court Justice John Paul

Stevens in a dissenting opinion, joined by Justices David Souter, Ruth Bader

Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer, observed that the Second Amendment is notable

for the “omission of any statement of purpose related to the right to use

firearms for [either] hunting or personal self-defense.”

This omission stands in contrast to the language of the constitution of the

long defunct Vermont Republic, and to similar wording added later to the

Pennsylvania state constitution.

Whatever the Second Amendment is about, or judicially interpreted to be about, 227 years after it was written, it was never about hunting, except the sort of hunting of fugitive slaves for which the Broxton Bridge Plantation in South Carolina became notorious in 1853, long before it became better known for hosting “tower shoots” of pheasants and pigeon shoots.

Return to Animal Rights Articles